The mundane future of smart new worlds

June 08 • thought • written by Timo

“There is a kind of sensor at the entrance to the parking lot”, a son-in-law of a family in Songdo, South Korea, explains. “So, if your car gets through the entrance, it gives an alarm to your apartment … Sometimes I feel, this is convenient, but sometimes you just want to park and maybe go for a drink … without other family members know that (sic)”.

He felt like his private habits were threatened by the alarm from the garage. The same alarm, which, ironically, had been intended to preserve privacy – that of people in the apartment – by warning that someone is on their way up.

But after a few weeks he will get used to it, and find another moment in the day to have a beer. He will adapt, just like with the other new services that flood our everyday lives, each one promising efficiency, safety, and convenience. We wondered, is it just small habits, like going for a drink, that are changed? Or is it ultimately our values and our physical spaces?

We took a look at the city of Songdo in the greater Seoul.* It is one of the first smart cities to be built from scratch and with leading participation from multinational companies. We spoke to families in "First World", one of Songdo's early housing estates, completed in 2010: "There is not the urbanity of Seoul here, but the housing is cheaper, equipped with the latest digital technology and the education is very good.”

Housing in Korea has a strong social and technological component in addition to the ownership aspect. Buying a flat that can be given to the son as a wedding present is considered an opportunity for social advancement and position in middle-class families. In addition, due to South Korea’s rapid transformation since the 1970s, from a rural to an industrialised and urbanised society, there is a strong belief in the technological feasibility of a better life.

However, with the rapidly advancing digitalisation of everyday life, things often turn out differently than expected; at least not in the way that developers, planners and visionary politicians have mapped out. This becomes very clear in Songdo, where internationally developed technology meets socio-cultural peculiarities. Also, with the triumph of the smartphone, the practical meaning of digitality has already radically changed in the relatively short development phase of the city since 2002.

Today Songdo is extraordinarily ordinary. It often turns out that the digitalisation that once felt so new only reinforces the social structures that were there long before: Family, social climbing, conventions of cohabitation and exclusive security thinking.

"The best advantage of living in Songdo is the security. Songdo is only connected by five bridges. Even if a crime breaks out, the criminal cannot leave Songdo by car if five bridges are closed." The smart city Songdo was built on an artificial island that functions like a conventional gated community. CCTV-monitored bridges separate the homogeneous and privileged middle class on the island from the relatively unprivileged surrounding districts of Incheon.

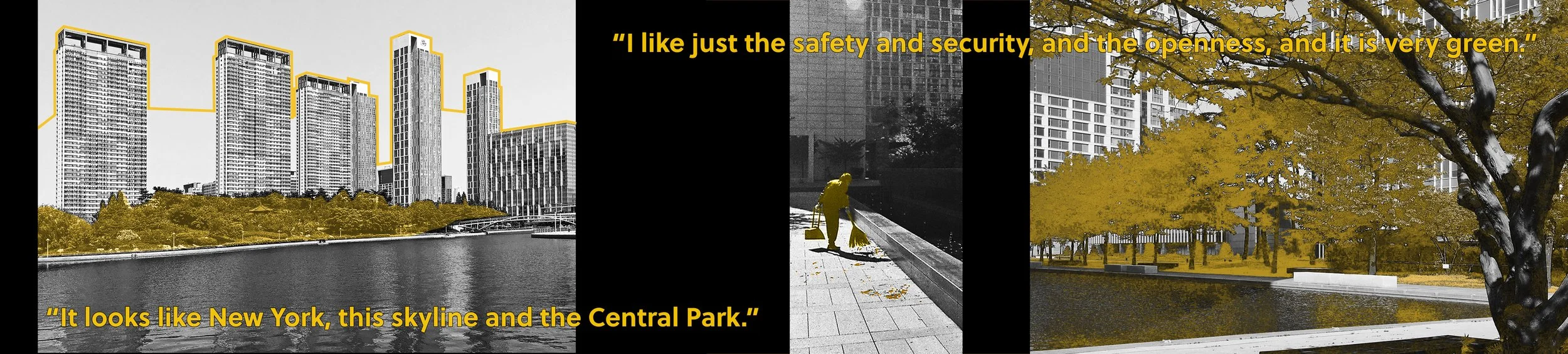

The city itself is again divided into different gated neighbourhoods, mostly in the form of grouped residential towers. The grid system, the skyline and the central park are strongly reminiscent of Manhattan. Except that in Songdo the streets are empty, clean and safe. And since there is no crime, the guards of the gated housing estates are now concerned with picking up litter and weeding. Green here means safe, and safe is green.

"I just like the safety and security, and the openness and it's very green, ...you feel like you're almost living in a semi-rural environment". These are open landscapes with free views and access. Only the imposing entrance gates with guards remind us of the physical enclosures of conventional gated communities: functionally superfluous, but emotionally very present, even without fences or walls.

We have CCTV for that. “Just no idea if they are even in operation or merely attached.” For as open as access from the outside may be, inside these communities new and insurmountable boundaries are quickly being established; by complex digital surveillance systems with smart cards, sensors, checkpoints and CCTV cameras, and even more so, by disciplined collective practices.

Many parents track their children with their smartphones. Since they have to form a virtual family group for this, they can now also monitor each other as a couple. In Songdo they can also supervise their children from home via a monitor. "The playground is a channel we can watch". As a matter of course, parents here become part of the digital surveillance system. And in doing so, they legitimise a new social reality that blurs the boundaries we are so familiar with, between supervisor and supervised, between public and private.

"Privacy? I haven't done anything bad, so it's fine. As long as I'm safe."

*Note: The research presented here was developed in an interdisciplinary research group as part of the Collaborative Research Centre “Refiguration of Spaces” at the Technical University Berlin and co-funded by the German Research Foundation. Our project “Smart Cities: Everyday Life in Digitalized Spaces” draws from sociology, urban design and cultural studies. It explores processes of everyday spatial constitution and their refiguration under conditions of selective changes in urban communication through the use of digital devices. The case under investigation was the South Korean city of Songdo. The research has been published in high-impact journals. Please see e.g., Bartmanski, D., Kim, S., Löw, M., Pape, T., & Stollmann, J. (2023). Fabrication of space: The design of everyday life in South Korean Songdo. Urban Studies, 60(4), 673-695.

all photos by Timo